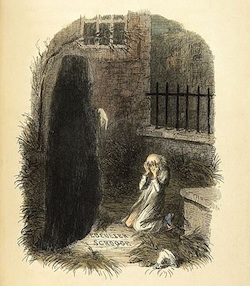

Today, two articles were published on A List Apart about ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) – The Accessibility of WAI-ARIA by Detlev Fischer and ARIA and Progressive Enhancement by Derek Featherstone. Like the ghosts in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, they present an accurate, though somewhat depressing picture of the current and potential future state of things.

The Ghost of ARIA Present

Scrooge entered timidly, and hung his head before this Spirit. He was not the dogged Scrooge he had been; and though the Spirit’s eyes were clear and kind, he did not like to meet them. “I am the Ghost of Christmas Present,” said the Spirit. “Look upon me.”

In Dickens’ classic, the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge the dismal state of present affairs. As the ALA articles detail in great length, ARIA support is quite a mess. While we’ve seen good adoption of ARIA support in some areas, it is still very buggy and not useful to the vast majority of screen reader users. The fault here lies primarily with browsers and screen readers.

In Dickens’ classic, the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge the dismal state of present affairs. As the ALA articles detail in great length, ARIA support is quite a mess. While we’ve seen good adoption of ARIA support in some areas, it is still very buggy and not useful to the vast majority of screen reader users. The fault here lies primarily with browsers and screen readers.

ARIA is supposed to alleviate the need for accessibility hacks, workarounds, fall-backs, and alternative versions. Instead, because of patchy support, these are the very things necessary in order to implement much of it.

Still, ARIA is new. In fact, it’s less than new – it’s not even a finalized W3C specification yet. Implementing ARIA into user agents is difficult, especially considering the limitations of the accessibility APIs on current operating systems. Despite this, we’ve seen ARIA implemented to varying extents in most modern browsers, many screen readers, and in authoring tools and scripting libraries. It is unreasonable to expect that ARIA will work perfectly right out of the box. However, unlike the ALA articles, I will not focus on the current state of ARIA, and think that developers for the most part shouldn’t either. Instead, we should be focusing on what we can and should do to ensure that support increases as we move forward.

What to do now?

Both articles recommend that great care be taken in implementing ARIA. This certainly is true. Detlev Fischer suggests that using anything more than the most basic of well-supported ARIA semantics will almost certainly make things worse for screen reader users. I, however, believe that there is much that can be done today to enhance web content with ARIA that can only make content more accessible on platforms that support it. And Derek Featherstone shows this to be true with several practical uses of ARIA to enhance already-accessible content. There are, however, some important points that I believe should be addressed.

Some things cannot be made accessible without ARIA!

These articles suggest only two courses of action: 1) don’t build it, or 2) build it so it remains accessible without end-user ARIA support. These, unfortunately, are not viable options for many modern web applications. We certainly should encourage the progressive enhancement approach to accessibility. We should build highly accessible web apps with all of the available and widely supported tools and markup available, and then use ARIA to make it even better. But this is not always possible for complex web applications – and Derek Featherstone demonstrates that it’s not even really possible right now with even very basic interactive elements such as a required form field.

The Ghost of ARIA Yet To Come

"The Phantom slowly, gravely, silently approached. When it came near him, Scrooge bent down upon his knee; for in the very air through which this Spirit moved it seemed to scatter gloom and mystery."

Developers will continue to innovate with or without accessibility. Because not building it is not an option and because some things cannot be made accessible without ARIA, developers are left with two options – build it potentially accessible with ARIA or build it perpetually inaccessible without ARIA.

Developers will continue to innovate with or without accessibility. Because not building it is not an option and because some things cannot be made accessible without ARIA, developers are left with two options – build it potentially accessible with ARIA or build it perpetually inaccessible without ARIA.

I believe that most developers want to make things accessible, particularly once they know how. ARIA allows them to do it right the first time. We must allow developers to focus on potential accessibility, rather than bogging them down with the complexities of current support. Implementing ARIA is not very complex, especially compared to scripting or even HTML5. But, understanding current ARIA support is a nightmare. Trying to implement ARIA detection and degradation where it is not supported is a nightmare that nightmares have. Developers try to avoid nightmares, so let’s not force one upon them.

If we take a hard-line approach and insist that developers wait for ARIA support (whatever that means) rather than implementing ARIA now despite today’s incomplete support, they will most often throw their hands in the air and build it without ARIA and accessibility at all.

This is especially true with the many web applications that are already in place – ones that will never be rebuilt with full accessibility, but that could be greatly improved by adding minor ARIA enhancements. By suggesting that full ARIA support and fallbacks are required, we are encouraging that these apps remain inaccessible into perpetuity.

While the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come convinced Ebenezer Scrooge to change, I fear that web app developers are not always so repentant – whether we like it or not, their future is pretty good with or without accessibility.

If you build it…

I once visited the baseball field where The Field of Dreams movie was filmed. A theme of this movie was, “If you build it, they will come.” With the current state of ARIA, we are telling developers, “Don’t build it, because some can’t currently come.” While our intentions are certainly noble – we don’t want to leave folks behind – the result of asking web developers to hold off on innovating until ARIA support improves is that developers will instead innovate anyways without ARIA support at all. The result is much worse accessibility.

I once visited the baseball field where The Field of Dreams movie was filmed. A theme of this movie was, “If you build it, they will come.” With the current state of ARIA, we are telling developers, “Don’t build it, because some can’t currently come.” While our intentions are certainly noble – we don’t want to leave folks behind – the result of asking web developers to hold off on innovating until ARIA support improves is that developers will instead innovate anyways without ARIA support at all. The result is much worse accessibility.

Now I’m not advocating that we simply forget about the many limitations of ARIA. The ALA articles outline many of these limitations ad nauseum. My point is that if we want ARIA to succeed, we must look beyond the limitations of today. We must advocate that people start building with it by the book now. This means building things to be as accessible as they can be, then using ARIA to make them better. And when ARIA is required for accessibility, do that, because it’s better than the alternatives.

If we focus on supporting ARIA as it is now, support will largely remain how it is now. We should instead advocate that developers build things following standards, increase our pressure on browser and assistive technology vendors to increase their support, and help users understand the increased accessibility they can experience by using standards-compliant web browsers and assistive technology. The future of ARIA is bright, but only if we make it so.

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,” said Scrooge. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change.”

Some thoughts on ARIA support detection

In his conclusion, Derek indicates that we “need to be able to detect ARIA support in assistive technology so that we know if ARIA is supported in those user agents.” While this initially seem like very appealing functionality, I believe that if this were possible (it isn’t, and probably won’t ever be), the results could be very damaging. The fact that we cannot detect assistive technology has resulted in significant increases to mainstream accessibility. An ability to detect assistive technology support would have potential to allow for complex enhancements to accessibility, but in reality, I fear it would lead to fragmentation of code and user experience at best, and “You must have JAWS 12+ to view this page” at worst.

I agree with you for the most part. I’d very much like to see some of the systems that are currently in the works adopt some level of ARIA implementation (if they are using or creating rich apps.

I think a small distinction needs to be made between those that should do it and those that have to do it accessible… and what is appropriate depends largely on that. A federal organisation “has” to do things in such a form that citizens have the best chance today to access content and because of this they may not be the best candidate to be an early adopter. Simply because their role needs to be to allow everyone to participate today (and not at some future date). I think that the private sector is a whole other ball of twine.

Jared — thanks for reading, and — more importantly — writing 🙂

Great piece — James posted a few quotes from your article as a comment on my article, so I’ve responded over there in the comments section with some follow up of my own.

How could this possibly be achieved while it’s literally impossible to detect if a given site is being visited with assistive technology?

Regarding ARIA support detection:

In a comment to my article on “A list apart”, James Craig pointed to a W3C proposal for “User Interface Independence for Accessible Rich Internet Applications”. http://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/wai-xtech/2010Aug/att-0079/UserInterfaceIndependence.html

That proposal includes “Assistive Technology Identification and Notification” to detect Screenreades, Magnifiers and Speech, including version information.

How exactly such information would be used, I am not sure. We probably do not want to see a repetition of forking for different makes and versions if it can be avoided.

James, what do you think are the chances of adoption of this proposal in future specs and standards? Ad if implemented, how do you assess the chances of wide adoption in the future web apps out there?

Great commentary Jared. Thanks so much for writing this; it gives me hope.

It’s a shame for users and developers alike that features such as this could not have been properly implemented almost universally a few years ago, rather than what may be a few years hence. When such techniques are made simple to implement and widely supported, developers have few excuses for omitting them. Generally, I feel like there is a lot of latency in web-related software development and the formation of web standards.